Lake Yaté

Lake Yaté Oui Poin tribe, La Foa

Oui Poin tribe, La FoaHistory, People, and Culture

in New CaledoniaThe history of New Caledonia

Lake Yaté

Lake YatéThe archipelago was discovered in 1774 by British navigator James Cook, who named the country “New Caledonia” because of the resemblance between the mountainous terrain of Grande Terre and his native Scotland. He noted that the country was inhabited by Melanesians (now more commonly known as Kanaks). On September 24, 1853, Admiral Fébvrier-Despointes took possession of the island on behalf of France, Britain having abandoned it. New Caledonia has been French since that date. The city of Nouméa, today the archipelago’s capital, was created in 1854.

In 1864, colonisation through settlement intersected with colonisation through incarceration. Napoleon III established the infamous ‘bagne’, housing around 5,000 communards (opponents of the political regime). Given New Caledonia’s distant location, the penitentiary colony provided a secure detention site for political dissidents from various French regimes. In an effort to populate New Caledonia, it was determined that both male and female prisoners would remain on the territory for a duration equal to their completed sentence. The penal colony dissolved in 1897. During this era, New Caledonia experienced several Kanak uprisings, most notably led by the esteemed chief Ataï in 1878.

Fort Teremba penal colony historic site, Moindou

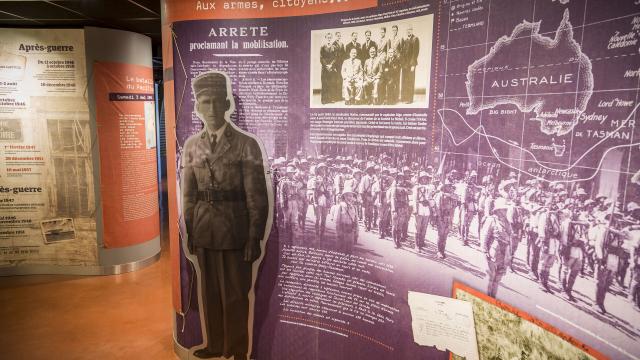

Fort Teremba penal colony historic site, Moindou World War II Museum in Nouméa, New Caledonia

World War II Museum in Nouméa, New CaledoniaDuring World War II, New Caledonia emerged as a strategic base for American forces engaged in the Pacific campaign. Over 50,000 American troops were stationed there. In 1946, New Caledonia officially became an overseas territory.

The 1980s bore witness to conflicts between advocates of independence and those in favour of remaining French. These tensions escalated into a widespread insurrection, culminating in the Ouvéa hostage crisis. This crisis compelled both sides to engage in negotiations and led to the Matignon Accords in 1988. These accords established a decade-long transitional status, ultimately culminating in a self-determination referendum. In 1998, the Nouméa Accord was ratified, granting substantial autonomy and postponing the final referendum regarding the archipelago’s institutional future. The most recent independence referendum was conducted on December 12, 2021, with the “no” vote prevailing with 96.50% of the ballots cast. This marked the conclusion of the Nouméa Accord era, ushering in a transition phase to determine New Caledonia’s new status within the French Republic, to be decided via a future referendum.

The three pillars of New Caledonia's economy

Serpentine from the Goro mine in Yaté, Grand Sud

Serpentine from the Goro mine in Yaté, Grand SudOn the economic front, in 1894, engineer Jules Garnier initiated the extraction of nickel ore. It wasn’t until after 1960 that nickel production entered a phase of expansion, greatly favouring the development of New Caledonia’s economy.

Today, New Caledonia’s economic foundation rests on three pillars: nickel extraction (along with magnesium, iron, cobalt, chromium, and manganese), financial transfers from metropolitan France, and tourism.

A land enriched by culture

New Caledonia thrives on the diverse cultures of its constituent peoples: Kanak, European, Asian, Polynesian, and more. With over 270,000 inhabitants, this archipelago pulsates with cosmopolitan vitality. Predominantly Christian, New Caledonia encompasses both Catholic and Protestant communities, along with representation from various other religions. In Kanak culture, Christianity harmoniously coexists with animist and polytheistic beliefs.

The Kanak languages are Austronesian in origin. There are currently 28 of them, to which we can add 11 dialects. The vast majority of Kanak people continue to speak the language of their region of origin. That said, the number of speakers per language varies widely, and some of them could disappear in the decades to come, despite a strong determination to keep this intangible heritage alive. Pwapwâ (Voh region) and Sîchë (Bourail / Moindou), for example, now have just a few dozen speakers. By contrast, Drehu (Lifou), Nengone (Maré), Xârâcùù (Canala / La Foa / Boulouparis), Paicî (Poindimié / Ponerihouen) and Ajië (Houaïlou / Poya) are spoken by several thousand people on a daily basis. For several years now, some of these languages have been taught as optional subjects in schools, and can be taken as a baccalaureate exam. The defence, promotion and evolution of Kanak languages are among the provisions of the Nouméa Accord (1998), and in 2007 led to the creation of an Academy of Kanak Languages.